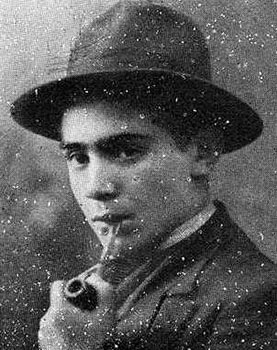

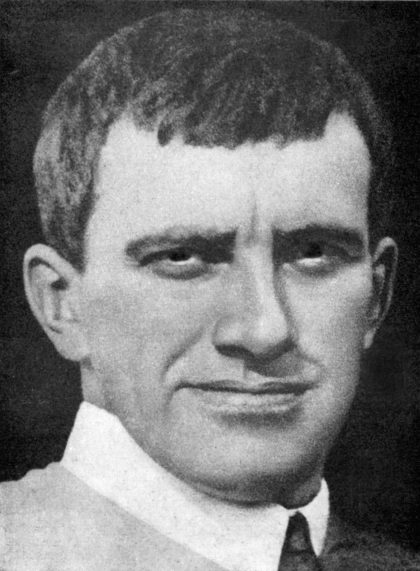

Mayakovsky Vladimir

Majakovskij, Vladimir Vladimirovic. – Poeta, autore drammatico e pittore russo (Bagdadi, od. Majakovskij, presso Kutais, 1893 – Mosca 1930). Grande innovatore, esercitò enorme influenza sui movimenti artistici russi d’avanguardia. Militante nel partito bolscevico, fu inizialmente pittore e fece parte del gruppo dei cubofuturisti; nel 1923 organizzò il LEF (Leuyj Front iskusstv “Fronte di sinistra delle arti”). Tra le opere: i poemi Oblako v štanach (“La nuvola in calzoni”) e Flejta-pozvonocnik (“ll flauto di vertebre”), entrambi del 1915; la commedia Misterija-Buff (“Mistero buffo”, 1917), sulle vicende della Rivoluzione russa; il poema Vladimir Il´ic Lenin (1924).

VITA

Ancora adolescente, svolse intensa attività politica nel partito bolscevico e fu arrestato tre volte. Dedicatosi poi allo studio delle arti figurative, fu espulso (1914) dall’Istituto di pittura, scultura e architettura di Mosca per la sua appartenenza al gruppo dei cubofuturisti. Nel 1913 apparve il suo primo libro, Ja! (“Io!”). Nel dic. 1913 interpretò a Pietroburgo, al teatro Luna Park, la propria tragedia Vladimir Majakovskij. Accolse la rivoluzione con entusiasmo e nel 1923 organizzò il LEF (Levyj Front iskusstv “Fronte di sinistra delle arti”), che raggruppò artisti, poeti, scenografi, registi, filologi vicini al futurismo, e pubblicò la rivista omonima. In quegli anni fu il simbolo di tutto ciò che v’era di moderno e di audace nell’arte sovietica. La campagna condotta contro di lui dalla critica di partito, le delusioni politiche e motivi amorosi lo spinsero al suicidio.

OPERE

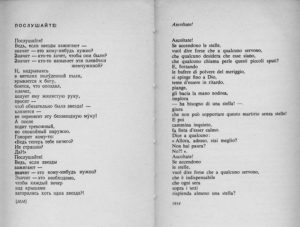

Strenuo innovatore, fuse le tendenze ribelli e anarchiche del futurismo con l’attività di tribuno e di agitatore durante la rivoluzione d’Ottobre. La sua opera maggiore prima della rivoluzione è il poema Oblako v štanach (“La nuvola in calzoni”, 1915), in cui il motivo d’amore e quello sociale s’intrecciano in una trama iperbolica, esasperata. Gli stessi accenti ritornano nei poemi Flejta-pozvonocnik (“Il flauto di vertebre”, 1915), Vojna i mir (“La guerra e l’universo”, 1917), Celovek (“L’uomo”, 1916-17). Le vicende della rivoluzione sono trasposte su un piano biblico nella commedia Misterija-Buff (“Mistero buffo”, 1917) e rivissute come scene di canti epici e di vignette popolari nel poema 150.000.000 (1921), che contrappone in un grottesco duello il gigante russo Ivan e Woodrow Wilson. Al tema d’amore M. tornò nei poemi Ljublju (“Amo”, 1922) e Pro eto (“Di questo”, 1923). La morte di Lenin gli suggerì il poema Vladimir Il´ic Lenin (1924) e il decimo anniversario della rivoluzione l’affresco epico Chorošo! (“Bene!”, 1927). Accanto a queste ampie composizioni, scrisse odi d’intonazione oratoria, versi di propaganda commerciale e politica, poesie satiriche, scenari cinematografici, pantomime, canovacci per scene di circo, commedie come Klop (“La cimice”, 1928) e Banja (“Il bagno a vapore”, 1929). L’influenza di M. sui movimenti artistici russi d’avanguardia fu enorme. M. era stato inizialmente pittore, e della sua attività figurativa, dopo che si era dedicato agli scritti e all’azione politica, sono importanti le ricerche tipografiche e compositive fatte in collab. con A. Rodcenko (pagine della rivista Lef, 1923 segg.).

(English)

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky 19 July 1893 – 14 April 1930 was a Russian Soviet poet, playwright, artist, and actor.

During his early, pre-Revolution period leading into 1917, Mayakovsky became renowned as a prominent figure of the Russian Futurist movement; being among the signers of the Futurist manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1913), and authoring poems such as A Cloud in Trousers (1915) and Backbone Flute (1916). Mayakovsky produced a large and diverse body of work during the course of his career: he wrote poems, wrote and directed plays, appeared in films, edited the art journal LEF, and created agitprop posters in support of the Communist Party during the Russian Civil War. Though Mayakovsky’s work regularly demonstrated ideological and patriotic support for the ideology of the Communist Party and a strong admiration of Lenin, Mayakovsky’s relationship with the Soviet state was always complex and often tumultuous. Mayakovsky often found himself engaged in confrontation with the increasing involvement of the Soviet State in cultural censorship and the development of the State doctrine of Socialist realism. Works that contained criticism or satire of aspects of the Soviet system, such as the poem “Talking With the Taxman About Poetry” (1926), and the plays The Bedbug (1929) and The Bathhouse (1929), were met with scorn by the Soviet state and literary establishment.

In 1930 Mayakovsky committed suicide. Even after death his relationship with the Soviet state remained unsteady. Though Mayakovsky had previously been harshly criticized by Stalinist governmental bodies like RAPP, Joseph Stalin posthumously declared Mayakovsky “the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch.”

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was born the last of three children in Baghdati, Kutaisi Governorate, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire. His father Vladimir Konstantinovich Mayakovsky, a local forester, belonged to a noble family and was a distant relative of the writer Grigory Danilevsky. Vladimir Vladimirovich’s mother Alexandra Alexeyevna (née Pavlenko), was a housewife, looking after the children – a son and two daughters, Olga and Lyudmila (their brother Konstantin died at the age of three).

The family had Russian and Zaporozhian Cossack descent on their father’s side and Ukrainian on their mother’s. At home the family spoke Russian. With his friends and at school Mayakovky used Georgian. “I was born in the Caucasus, my father is a Cossack, my mother is Ukrainian. My mother tongue is Georgian. Thus three cultures are united in me”, he told the Prague newspaper Prager Presse in a 1927 interview. Georgia for Mayakovsky remained the eternal symbol of beauty. “I know, it’s nonsense, Eden and Paradise, but since people sang about them // It must have been Georgia, the joyful land, that those poets were having in mind”, he wrote later.

In 1902 Mayakovsky joined the Kutais gymnasium where, as a 14-year-old he took part in socialist demonstrations at the town of Kutaisi. His mother, aware of his activities, apparently didn’t mind. “People around warned us we were giving a young boy too much freedom. But I saw him developing according to the new trends, sympathized with him and pandered to his aspirations”, she later remembered. After the sudden and premature death of his father in 1906 (he pricked his finger with a rusty pin while filing papers and died of blood poisoning) the family — Mayakovsky, his mother, and his two sisters — moved to Moscow after selling all their movable property.

In July 1906 Mayakovsky joined the 4th form of the Moscow’s 5th Classic gymnasium and soon developed a passion for Marxist literature. “Never cared for fiction. For me it was philosophy, Hegel, natural sciences, but first and foremost, Marxism. There’d be no higher art for me than “The Foreword” by Marx, he recalled in the 1920s in his autobiography I, Myself. In 1907 Mayakovsky became a member of his gymnasium’s underground Social Democrats’ circle, taking part in numerous activities of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which he, given the nickname “Comrade Konstantin”, joined the same year. In 1908, the boy was dismissed from the gymnasium because his mother was no longer able to afford the tuition fees. For two years he studied at the Stroganov School of Industrial Arts, where his sister Lyudmila had started her studies a few years earlier.

In 1911 Mayakovsky enrolled in the Moscow Art School. In September 1911 a brief encounter with fellow student David Burlyuk (which nearly ended with a fight) led to lasting friendship and had historic consequences for the nascent Russian Futurist movement. Mayakovsky became an active member (and soon a spokesman) for the group Hylaea (Гилея), which sought to free the arts from academic traditions: its members would read poetry on street corners, throw tea at their audiences, and make their public appearances an annoyance for the art establishment.

On 17 November 1912, Mayakovsky made his first public performance on stage of the Stray Dog artistic basement in Saint Petersburg. In December of that year his first published poems, “Night” (Ночь) and “Morning” (Утро) appeared in the Futurists’ Manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, signed by Mayakovsky, as well as Velemir Khlebnikov, David Burlyuk and Alexey Kruchenykh, calling among other things for… “throwing Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, etc, etc, off the steamboat of the modernity.”

In October 1913 Mayakovsky gave the performance at the Pink Lantern café, reciting his new poem “Take That!” (Нате!) for the first time. The concert at the Petersburg’s Luna-Park saw the premiere of the poetic monodrama Vladimir Mayakovsky, with the author in a leading role, stage decorations designed by Pavel Filonov and Iosif Shkolnik. In 1913 Mayakovsky’s first poetry collection called I (Я) came out, its original limited edition 300 copies lithographically printed. This four-poem cycle, handwritten and illustrated by Vasily Tchekrygin and Leo Shektel, later formed Part One of the 1916 compilation Simple as Mooing.

In December 1913 year Mayakovsky along with his fellow Futurist group members embarked on the Russian tour, which took them to 17 cities, including Simferopol, Sevastopol, Kerch, Odessa and Kishinev. It was a riotous affair. The audiences would go wild and often the police stopped the readings. The poets dressed outlandishly, and Mayakovsky, “a regular scandal-maker” in his own words, used to appear on stage in a self-made yellow shirt which became the token of his early stage persona. The tour ended on 13 April 1914 in Kaluga and cost Mayakovsky and Burlyuk their education: both were expelled from the Art school for their public appearances deemed incompatible with the school’s academic principles. They learned of it while in Poltava from the local police chief, who chose the occasion as a pretext to ban the Futurists from performing on stage.

Having won 65 rubles in lottery, in May 1914 Mayakovsky went to Kuokkala, near Petrograd. Here he put the finishing touches to A Cloud in Trousers, frequented Korney Chukovsky’s dacha, sat for Ilya Repin’s painting sessions and met Maxim Gorky for the first time. As World War I began, Mayakovsky volunteered but was rejected as “politically unreliable”. He worked for a time at the Lubok Today company which produced patriotic lubok pictures, and in the Nov (Virgin Land) newspaper, which published several of his anti-war poems (“Mother and an Evening Killed by the Germans”, “The War is Declared”, “Me and Napoleon” among others).In summer 1915 Mayakovsky moved to Petrograd where he started contributing to the New Satyrikon magazine, writing mostly humorous verse in the vein of Sasha Tchorny, one of the journal’s former stalwarts. Then Maxim Gorky invited the poet to work for his journal, Letopis (Chronicle).

In June of that year Mayakovsky fell in love with a married woman, Lilya Brik, who eagerly took upon herself the role of a “muse”. Her husband Osip Brik seemed not to mind and became the poet’s close friend; later he published several books by Mayakovsky and used his entrepreneurial talents to support the Futurist movement. This love affair, as well as his impressions of World War I and Socialism, strongly influenced Mayakovsky’s best known works: A Cloud in Trousers (1915), his first major poem of appreciable length, followed by Backbone Flute (1915), The War and the World (1916) and The Man (1918).

When his mobilization form finally arrived in the autumn of 1915, Mayakovsky found himself unwilling to go to the frontlines. Assisted by Gorky, he joined the Petrograd Military Driving school as a draftsman and was studying there until early 1917. In 1916 Parus (The Sail) Publishers (again led by Gorky), published Mayakovsky’s poetry compilation called Simple As Mooing.

Mayakovsky embraced the Bolshevik Russian Revolution wholeheartedly and for a while even worked in Smolny, Petrograd, where he saw Vladimir Lenin and was rubbing shoulders with the revolutionary soldiers. “To accept or not to accept, there was no such question… [That was] my Revolution,” he wrote in I, Myself autobiography. In November 1917 he took part in the Communist Party’s Central committee-sanctioned assembly of writers, painters and theater directors who expressed their allegiance to the new political regime. In December that year “The Left March” (Левый мар,1918) was premiered at the The Navy Theater, with sailors as an audience.

In 1918 Mayakovsky started the short-lived Futurist Paper. He also starred in three silent films made at the Neptun Studios in Petrograd he had written scripts for. The only surviving one, The Lady and the Hooligan, was based on the La maestrina degli operai (The Workers’ Young Schoolmistress) published in 1895 by Edmondo De Amicis, and directed by Evgeny Slavinsky. The other two, Born Not for the Money and Shackled by Film were directed by Nikandr Turkin and are presumed lost.

On 7 November 1918 Mayakovsky’s play Mystery-Bouffe was premiered in the Petrograd Musical Drama Theatre. Representing a universal flood and the subsequent joyful triumph of the “Unclean” (the proletariat) over the “Clean” (the bourgeoisie), this satirical drama was re-worked in 1921 to even greater popular acclaim. However, the author’s attempt to make a film of the play failed, the Moscow Soviet finding its language “incomprehensible for the masses.”

In March 1919 Mayakovsky moved back to Moscow where Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Collected Works 1909–1919 was released. The same month he started working for the Russian State Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) creating — both graphic and text — satirical Agitprop posters, aimed mostly at informing the country’s largely illiterate population of the current events. In the cultural climate of the early Soviet Union, his popularity grew rapidly, even if among the members of the first Bolshevik government, only Anatoly Lunacharsky supported him; others treated the Futurist art more skeptically. Mayakovsky’s 1921 poem, 150 000 000 failed to impress Lenin, who apparently saw in it little more than a formal futuristic experiment. More favourably received by the Soviet leader was his next one, “Re Conferences” which came out in April.

A vigorous spokesman for the Communist Party, Mayakovsky expressed himself in many ways. Contributing simultaneously to numerous Soviet newspapers, he poured out topical propagandistic verses and wrote didactic booklets for children while lecturing and reciting all over Russia.

In May 1922, after a performance at the House of Publishing at the charity auction collecting money for the victims of Povolzhye famine, he went abroad for the first time, visiting Riga, Berlin and Paris where he visited the studios of Léger and Picasso. Several books, including The West and Paris cycles (1922–1925) came out as a result

From 1922 to 1928, Mayakovsky was a prominent member of the Left Art Front (LEF) he helped to found (and coin its “literature of fact, not fiction” credo) and for a while defined his work as Communist Futurism (комфут). He edited, along with Sergei Tretyakov and Osip Brik, the journal LEF, its stated objective being “re-examining the ideology and practices of the so-called leftist art, rejecting individualism and increasing Art’s value for the developing Communism.” The journal’s first, March 1923, issue featured Mayakovsky’s poem About That (Про это). Regarded as a LEF manifesto, it soon came out as a book illustrated by Alexander Rodchenko who also used some photographs made by Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik.

In May 1923 Mayakovsky spoke at a massive protest rally in Moscow, in the wake of Vatslav Vorovsky’s assassination. In October 1924 he gave numerous public readings of the 3,000-line epic Vladimir Ilyich Lenin written on the death of the Soviet Communist leader. Next February it came out as a book, published by Gosizdat. Five years later Mayakovsky’s rendition of the third part of the poem, at the Lenin Memorial evening in the Bolshoi Theatre ended with 20-minutes ovation. In May 1925 Mayakovsky’s second trip took him to several European cities, then to the United States, Mexico and Cuba. The book of essays My Discovery of America came out later that year.

In January 1927 the first issue of the New LEF magazine came out, again under Mayakovsky’s supervision, now focusing on the documentary art. In all, 24 issues of it came out. In October 1927 Mayakovsky recited his new poem All Right! (Хорошо!) for the audience of the Moscow Party conference activists in the Moscow’s Red Hall. In November 1927 a theatre puction called The 25th (and based upon the All Right! poem) was premiered in the Leningrad Maly Opera Theatre. In summer 1928, disillusioned with LEF, he left both the organization and its magazine.

In 1929 the publishing house Goslitizdat released The Works by V.V. Mayakovsky in 4 volumes. In September 1929 the first assembly of the newly formed REF group gathered with Mayakovsky in the chair. But behind this façade the poet’s relationship with the Soviet literary establishment was quickly deteriorating. Both the REF-organized exhibition of Mayakovsky’s work, celebrating the 20th anniversary of his literary career and the parallel event in the Writers’ Club, “20 Years of Work” in February 1930, were ignored by the RAPP members and, more importantly, the Party leadership, particularly Stalin whose attendance he was greatly anticipating. It was becoming evident that the experimental art was no longer welcomed by the regime, and the country’s most famous poet irritated a lot of people.

Two of Mayakovsky’s satirical plays, written specifically for Meyerkhold Theatre, The Bedbug (1929) and (in particular) The Bathhouse (1930) evoked stormy criticism from the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. In February 1930 Mayakovsky joined RAPP, only to find himself labeled poputchik which from the days of Lenin amounted to a potentially deadly political accusation. The smear campaign was started in the Soviet press, sporting slogans like “Down with Mayakovshchina!” On 9 April 1930 Mayakovsky, reading his new poem “At the Top of My Voice”, was shouted down by the student audience, for being “too obscure.”