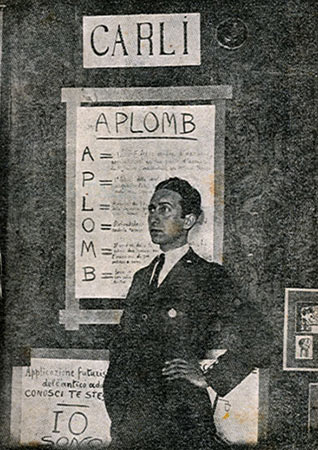

Ginanni Maria

Maria Ginanni (1891-1953)

Alla metà degli Anni Dieci, attirata dalla cerchia cerebralista intorno a Emilio Settimelli, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti e i fratelli Ginanni Corradini (Bruno Corra e Arnaldo Ginna) si trasferì a Firenze, dove, come redattrice e autore, avrebbe maggiormente influenzato il giornale „L’Italia Futurista” fin dalla fondazione nel 1916. Di fatto, quasi in ogni volume Maria Ginanni – come si avrebbe chiamato dopo il matrimonio con Arnaldo Ginna – prese la parola, sia con poesie, prose o riflessioni critici.

Degno di nota pare il fatto che la autrice lodatissima dai colleghi (Marinetti: “Prima scrittrice d´Italia”, „Il più formidabile genio che abbia l`Italia”) non si chiamò mai espressamente “futurista”, ma apparentemente aspirava sempre a tenere la propria indipendenza artistica.

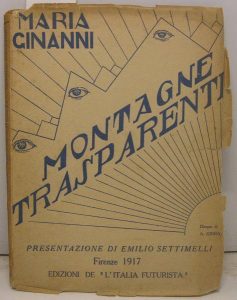

Nel 1917 Ginanni divenne editrice della serie “Libri di valore” che esce nell’ambito di „L’Italia futurista” e che venne aperto con la pubblicazione della sua propria antologia die prose „Montagne trasparenti” .

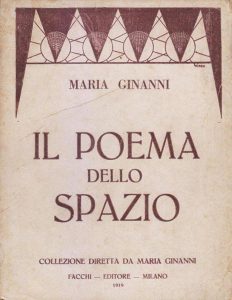

Dopo la fine dell’Italia Futurista Ginanni è una dei cofondatori della rivista „Lo specchio dell’ora“, del quale usciranno però solo due volumi. Riprende la sua attività come redattrice presso Facchi a Milano, dove nel 1919 esce il suo secondo volume di poesie „Il poema dello Spazio“.

Come la maggior parte dei suoi contemporanei Maria Crisi non percepì le esperienze spirituali come opposizione ma piuttosto come completamento rispetto alle scienze naturali.

Avenne così che, mentre studiava matematica a Roma, cominciò a frequentare anche i circoli spiritistici intorno a Annie Besant e la Società teosofica romana.

La prosa lirica di Maria Ginanni ruota intorno alla trascendenza sinestetica di mondi moderni (si guardi, per esempio, i titoli „Luci trasversali“, „Trasparenze“, „Novelle colorate“).

L’interiorizzazione e soggettivazione di osservazioni minuziose si scioglie in esperienze di limite, che infine possono essere considerate mezzi di autoriconoscenza.

Negli anni Venti Maria Ginanni sposa Ludovico Toeplitz, con il quale pubblicherà due libri in comune, che però rappresentano un certo abbandono delle tendenze futuriste.

ALCUNE POESIE DI MARIA GINANNI Folata d' azzurro Gran folata d'azzurro sull'anima. Per essa ogni cosa interiore vibra intensamente. È forza della mia giovinezza! È riso! Sonoro come cascata di oro a grani rimbalzante sulle pareti di acciaio dei muscoli. L'oro trasportato dalla folata improvvisa sprizza da tutti i cerchietti verdi spalanca i coni di viola, inonda le arterie di rosso, irrompe e precipita nella chiesa che trema tutta e vibra sotto la fragorosa scossa della pioggia metallica. Ma questa nuova pressione spezza le pareti: la chiesa crolla, s'abbatte, le tartarughe sono sepolte. Tutto è scoppio di luce formidabile. Ho per capelli dei fulmini! Paesaggio interno L'anima a fondo bianco. Cerchietti di verde. (Assomigliano ad iridi di uccelli fantastici che vogliano bucare, anzi sbucare la monotonia del cielo, vividi, mobilissimi, guizzanti). Filettature d'oro e d'argento. (Si attaccano al sonno della nebbia per merlettarlo di sorriso). Coni di viola, lunghi, lunghissimi. (Montano, montano, respirano oltre la nebbia, oltre la vita, col fiato di infinite boccucce simili a quelle dei pesci assonnati boccheggianti nell'acqua verdemente immota e opprimente delle vasche). Rosso. (Rosso del mio sangue che vuol precipitarsi sulla luna viscida per riscaldarla avvolgendola in un manto di vita, che sprizza sui fiori malinconicamente velati per renderli vibranti di palpito). Il rosso serpeggia sul fondo bianco su cui galleggiano i cerchietti verdi, roteanti vertiginosamente nella trama delle righe d'oro e d'argento: si appuntano poi come stelline sui lunghi coni viola e trasformano la mia anima in una tavola bianca su cui son posati dei fantastici cappelli di fata: linee d'oro e d'argento la rigano di una pioggia luminosa. da Montagne trasparenti, con presentazione di Emilio Settimelli, Firenze, Edizioni di «L'Italia Futurista», 1917

(English)

Sica, Paola – Maria Ginanni: futurist woman and visual writer – 2002

Maria Ginanni, called Maria Crisi before her marriage to Count Arnaldo Ginanni-Corradini (who adopted Ginna as his pseudonym), made a major contribution to Florentine Futurism. She promoted cultural debates, collaborated in publishing the journal L’Italia futurista (1916-1918), and supervised production of the homonymous editions aimed at diffusing new lyric and fantastic works. In addition to this, she wrote works with a strong visual component, such as Montagne trasparenti (1917) and Il poema dello spazio (1919). (1) By elaborating on Marinetti’s belief in action and violence, his glorification of the machine and his rejection of the past, Ginanni, like other Florentines, cultivated an interest in occultism and dream, but with a cerebralism that was more pronounced. (2)

Despite Ginanni’s substantial impact on the Florentine movement, recent criticism on Futurist women says little about her. Most of this criticism has focused on such figures as Valentine de Saint Point, Benedetta and Enif Roberts. (3) Ginanni may be less often considered because, even though, like others, she gave direction to the politics of the movement, she expressed her opinions on gender issues, in particular, in a less provocative way. Another reason may be that her creative technique fostered a certain independence from the rest of her group. Emilio Settimelli made note of Ginanni’s singular voice when, in the preface to her Montagne trasparenti, he wrote: “Dinanzi a noi futuristi ella si trova in una posizione unica…. Aderira … finalmente al futurismo? Oppure nel suo orgoglio sconfinato e nella sua chiaroveggenza abbozza gia linee di un nuovo movimento piu vasto e tutto suo?” (17).

In many studies on Futurism, especially those with a feminist approach, Ginanni is only marginally noted, either for her editorial work, or for having supervised, while standing aloof, a lively debate on sexual roles. She had, in fact, supported the protests of Futurist women who, in the column “Donne, amore e bellezza” of the Italia futurista, had attacked Marinetti’s provocative writings on women, in particular, his Come si seducono le donne published in 1917. (4) Analyses that are based more on style than politics have tended to focus on her creative writing. Most of them note Ginanni’s tendency to write fragments of poetic prose, (5) and make much of her recurrent use of figurative and dream-like images. (6) Many critics assert that her work anticipates the dawn of Surrealism. (7) Others maintain that her technique is analogous to that of the abstract painters. (8)

A reconsideration of Maria Ginanni through an analysis of her articles and, above all, her creative writings, allows us to understand her idea of a new woman and new writer. On one hand, exploring Ginanni’s conception of a new woman enriches previous accounts of Futurist sexual politics in that her woman distinguishes herself from that proposed by other Futurist women, and, at the same time, ambivalently responds to the mysoginist agenda proposed by Futurist male counterparts. The identity constructed by Ginanni is in fact considered as the product of a sexed and gendered individual who responds to a specific society and to specific power relations. Close reading of Ginanni’s creative work in the context of Avant-Garde aesthetics, on the other hand, allows a grasp of the relation between her concept of the self and her singular visual writing technique. Aesthetic signs are here conceived as results of cultural and historical conventions in which individuals are embedded, hence they enclose ideological messages. (9)

From an analysis of the texts, the main drive that leads Ginanni to the shaping Of her new woman is her desire for power, for the exceptional, and for the absolute. This desire presupposes rejection of what is bourgeois or mass-produced; a dismissal of differences of race and nationality; a refusal to acknowledge possession of a sexed and gendered body, which is translated into its negation or transfiguration; and, ultimately, a defiant denial of aging and of death. This desire generates the image of a super woman who embraces the new possibilities offered by technology, strives to provoke events, and even aspires to dominate time and space. The impetus of this woman, however, tends to be curbed when she comes to terms with the world of men. At that point, she often becomes an imperfect man, or a matrix of virility.

While creating her model, Ginanni accepts and expands the definition of the virile woman proposed a few years earlier by fellow Futurist Valentine de Saint Point. The women that Saint Point describes in the “Manifeste de la femme futuriste” are exceptional creatures who distinguish themselves from the masses. In them, as in superior men, masculine traits prevail over feminine (14-15). These women are either mothers or lovers, without possibilities of changing or joining the two roles. A “mere” [mother], Saint Point explains, “avec du passe fait de l’avenir” [with the past makes the future]; an “amante … dispense le desir qui entraine vers le futur” (20; lover … distributes the desire which drags toward the future). Ginanni’s women are an elaboration of both types together, with particular emphasis on the patriotic mother.

When, in a series of articles published in Italia futurista, Ginanni refers to the Italian history of her time, she assumes the voice of a strong woman who approves of an aggressive nationalism and who, from a private space, encourages heroic men engaged in war. (10) She praises an officer and his men because they repelled a German submarine with the one cannon on their little craft. She exclaims: “Grandi marinai d’Italia provati dal coraggio piu eroico. Con voi si vincono i sottomarini!” (“Come si vincono i sottomarini,” 18 Mar. 1917: 1). She thanks General Luigi Cadorna for having conquered Gorizia, and for having foretold Italian victory in a recent speech (“L’invito a Hindemburg,” 3 Apr. 1917: 1). Finally, she admires the boldness of Marinetti, who was wounded by Austrian machine-gun fire. Significantly, in writing about the event, she does not describe Marinetti’s wounded body, but his healthy body, “dai nervi temprati, [su cui] si e infranta impotente e flaccida [la mitraglia austriaca]” (“Marinetti ferito in guerra,” 2 May 1917: 1). (11) Marinetti’s vulnerability is projected onto the weapon that caused the injury, while, at the same time, the metallic resilience of bullets is shifted onto his male body. With these articles Ginanni begins to create her fiction of gender. In these specific cases, she becomes the invisible narrator of a male power that is indestructible.

During other reflections upon the war, Maria Ginanni expands her ideas of female roles. At times, she argues that traditional conceptions of women are unfairly limiting when they impose exclusion from the field of battle. In her article on Marinetti, she admits “[di] odiare i [suoi] abiti di donna che [le] vietano di prendere il [suo] posto” (1). At other times, she implies that, when women are perceived as creators, they can achieve positions of supreme power and can serve in public spaces traditionally reserved for men. But creators of what? Given Ginanni’s tendencies as discussed above, the answer is evident. Women should be the creators of a perpetual Italian virility. As she writes in “Cannoni d’Italia’:

Li ho visti costruire nelle nostre acciaierie formidabili, i cannoni

d’Italia, ed ho sentito per loro la forza di ardore di una donna dinanzi

all’essere creato dal suo sangue.

Si, i figli ed i cannoni d’Italia sono nati dalle donne d’Italia! … Sono

esse, sono esse stesse ora nelle nostre officine a plasmare il nostro

acciaio per noi…. Adorate le nostre bombarde agili, magnetiche

napoleoniche Vibranti del nostro sangue maschio e guerriero. (1)

Women are glorified as reproducers of war machines and of soldiers. At the same time, they are lauded as inexhaustible sources and extensions of technology and virility. In taking this position, Ginanni, like other Futurist women, employs what Barbara Spackman defines as a “rhetoric of virility,” namely a “phallocentric discourse” in which women “efface their difference and laud their approximation of a masculine ideal” (“Fascist Women and the Rhetoric of Virility,” Mothers of Invention 104). Ginanni’s woman, however, also shows something else: her desire to become supra-human.

These qualifies prefigure traits evident in the feminine model which Ginanni later created in her poetic prose: a model that still reveals a strong desire for power, but that challenges dominant feminine ideals constructed by Futurist men. Such a model is related to the starkly masculine, multiplied man described by Marinetti in “L’homme multiplie et le regne de la Machine,” in Le futurisme of 1911. In his essay, Marinetti predicts the coming of a new supra-human being born from the union of man and machine who may be seen as a product of Henri Bergson’s vitalism, Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the superman, and a Messianic vision devoid of moral content. (12) Marinetti declares that, with the new multiplied man, “seront abolis la douleur morale, la bonte, la tendresse et l’amour, seuls poisons corrosifs de l’intarissable energie vitale” (112-13; moral pain, goodness, tenderness and love will be abolished, being the sole corrosive poisons of the inexhaustible vital energy). Without sentiments, “la copulation” [copulation] will be intended solely for “la conservation de l’espece” [conservation of the species]; nobody will ever experience “la tragedie de la vieillesse et de l’impuissance” (115; the tragedy of old age and impotence). This new man will be able “d’exterioriser sa volonte de sorte qu’elle se prolonge hors de lui comme un immense bras invisible; [avec lui], le Reve et le Desir … regneront souverainement sur l’espace et sur le temps domptes” (113; to externalize his will in a way that it extends outside himself like a huge invisible arm; [with him], Dream and Desire will sovereignly rule over subdued space and time). In response to Marinetti’s multiplied man, Ginanni envisions a new self-sufficient female being who can overcome the limits imposed by her human nature, and assume the omnipotence and the reproductive power of a deified machine. By negating her connections to reality, she intends to dominate time and space, and to abandon herself to her vital impulses by following dreams and desires.

In order to avoid a direct confrontation with male discourse, Ginanni often speaks of bodies as limits, and deliberately omits reference to differences of gender and sex. In “Consigli a Dio” (Italia futurista 10 Aug. 1916: 1), she reduces her body to “un utensile [che e] rimasto quasi invariato” in all ages and societies. She declares that, to make it more functional, she would like “[scomporlo] nei suoi pezzi con tre o quattro movimenti decisivi e veloci.” To the relative invariability of her body, she opposes the enormous “maravigliosa evoluzione [della] psiche umana,” which, for her, is more fully developed in persons who belong to her race. In pressing her point, she claims:

Se voi osservate il corpo di un primitivo e quello dell’essere piu

raffinato e poi la religione di un feticcio e quella di un individualista

moderno voi vedrete il grande squilibrio nella intensita delle due

evoluzioni.

Come e quanto l’anima [dell’individualista] e stata piu geniale nel

trasformare le sue vesti e il suo ambiente! (1)

With her idea of a more evolved soul in certain races, deriving from an established hierarchy of values underpinning an imperialist and patriarchal ideology, Ginanni envisions a more fluid female self and offers deep insight into the feminine ideal. Paradoxically (and unavoidably), this idea threatened to erode these distinctions based on gender and race that were an integral element of Italy’s nationalistic Zeitgeist.

The presence of the multiplied woman, or rather, the disembodiment of the multiplied woman prevails in Ginanni’s creative writing. Descriptions of bodies are conspicuously absent, nor are direct sexual characterizations included. The most frequently mentioned bodily parts are brains, heads, eyes, cells, sinews: namely, the elements of an impersonal biological apparatus that alternatively allude to a female subject or to a boundless universe in which such a subject seems to be suspended, often in search for some revelation. At other times, the physical element is wholly excluded. Instead, her vital rhythms, like sobs and breaths, manifest themselves in synchrony with the rhythms of nature reflected in the instinctual, elemental lives of birds, fire-flies and crickets. These rhythms provide orientation for the subject adrift in a universe, which, like the night and the sky, is vast, mysterious and infinitely rich in potential. In “La piazza del tempo” of Montagne trasparenti, for instance, the noise of crickets is transformed into “punte d’acciaio [che si incuneano] fittamente nell’inconsistente disfacimento della … fuga [nel] vuoto [dell’io]” (22).

The nerves and organs cited in Ginanni’s work usually symbolize sensorial thresholds. They provide receptors for an elemental force that is subject only to laws that transcend the logical sequence of a mimetic representation. As allusions, these isolated physical elements educe awareness of the swift and discontinuous flow of modern life; they suggest infinitely many alternatives simultaneously offered by the primal realm of freedom that she depicts. As an example, in “I ponti delle cose” in Montagne trasparenti, a feminine subject initially observes herself from an external point of view and sees “la [sua] enorme testa sola … sospesa in aria … con le labbra assetate e gli occhi magnetizzati …” (141). Such parts of the body are put in contrast with a “crepuscolo violaceo e rovinoso” and they yearn for “cose irraggiungibili per milioni di strade che non finiscono….” Hence, the sharp and delimited images evoked by the words “testa,” “labbra” and “occhi” generate vague and unlimited images called up by the expressions “cose irraggiungibili” and “milioni di strade che non finiscono.” What was particular becomes general; what was human and feminine transforms itself into the suprahuman and the asexual; what was figurative tends toward abstraction.

Later on, this perspective is inverted. References to the body vanish; the subject’s soul appears, and it mirrors the vastness and that depth that initially characterized an external universe. This soul is depicted in a strongly visual way. It is “una serie indefinita di acque marine cristallizzate come fragili tele parallele di un vasto teatro immaginario.” By hinting at a difference between “ordinary” and “special” people, these “tele” are seen as “opache … per tutti gli altri,” whereas they are “vitree and continuamente spalancate su lontananze indefinite” (141) for the subject. By following the laws of osmosis, here, as in other works by Ginanni, the super woman’s soul and its surroundings interpenetrate through the permeability of her body; they influence each other. Descriptions of figures that become fluid from being circumscribed, or their repetition, evoke the subject’s different sensations in a hypnotic unfolding.

In their examination of Ginanni’s creative writing, Anna Nozzoli and Lucia Re maintain that the major emphasis is an obsessive transfiguration of sexual themes, phallic images, or copulation itself. (13) It is true that in both Montagne trasparenti and Il poema dello spazio such transfigurations appear. But these are incidental, and precisely because they are transfigurations, it is impossible to say with certainty what it is they are alluding to. In the section “Montagne trasparenti” of the homonymous work, for example, the image of a “tronco nero gettato dentro di te” (99), which is so troubling for the subject, is seen by Nozzoli as a “travestimento dell’atto sessuale” (51), and by Re as a “totemic veneration of the phallus” (263). But, in the original, the log is placed “dentro di te,” and “te” alludes to a park where the protagonist finds herself. Such a log is not “dentro di me,” with “me” referred to the subject, as both critics erroneously transcribe in their quotation. The image of this log appears in a section of the work in which the park is depicted both as a place of sacrifice and of revelations. While the log may symbolize in some way sexual ambivalence, attraction and revulsion, it clearly represents an object of veneration for the subject, who, shortly later, attempts in vain to reconcile “Commozione” and “cervello,” in order to seize the “vita-enigma” of the park (100).

The fusion of senses and intellect recurs as a central theme in other poetic prose works by Ginanni. This fusion discloses the overcoming of a present that is based on a linear logic of events, and is perceived as mediocre because of its repetition and its necessity. Senses and intellect also allow the recognition and establishment of authentic human relationship among super-men and super-women who embrace a similar philosophy of life. Ginanni publicly celebrates her own circle of superhumans, especially in Poema dello spazio, where she dedicates individual prose poems to women friends: Augusta Sormani, Nessie Cappelli, Vittoria di Sermoneta, Rosa Rosa and others. She endows them with titles of nobility, “contessa,” “marchesa,” “duchessa,” or with adjectives like “geniale,” that is with terms implying either social or intellectual distinction. In “Solitudini spirituali,” dedicated to Augusta Sormani, Ginanni at first records a solitary exploration of her own soul (11); then she recalls the necessity of embarking on relationships with kindred “anime,” to rejoice at such exploration, or “[per] scorrere le esalazioni piu fuggevoli dell’altro” (14). Ginanni believes that when such relationships (without distinction of sex) are genuine, their souls connect and transcend the limits of their bodies (15). An embrace occurs, but it is spiritual, and it seems to encompass a common superior knowledge.

In Poema dello spazio, the frequent doubts of the subject as to whether she will be able to attain superior knowledge are apparent. (14) (It is significant that this work was published in 1919, immediately after the Great War. It appeared at a historical moment in which, for many people, the grim consequences of the conflict contrasted starkly with their former bellicose exuberance and their excessive toast in recent technological discoveries.) The super woman’s will to power in Ginanni’s Poema still persists; however, it is often hindered. Occasionally, when this exceptional protagonist abandons herself to an impetus of elevation, she admits to being able to find only partial answers to her questions. She declares that she often feels like a bewildered “piccolo atomo” in the universe. Furthermore, her sense of permeability and dispersion that so frequently makes her rejoice, may as frequently leave her perplexed. She states with regret that “non possiamo neppur sapere dove la nostra interiorita finisce” (“Solitudini spirituali” 19). The protagonist of Ginanni’s Poema eventually admits to living in contradiction. At times, she trusts her capability; at other times, she does not. In her, “due esseri profondi e distinti [coesistono]”: her “cervello analitico” and her “spirito entusiasta” (“Superateismo” 41).

Whereas in Montagne trasparenti religious elements rarely appear (and where they do appear they are emptied of their message; the image of a church, for instance, is not a direct reference to a transcendental entity but is part of an unreal interior landscape, 38-39); in Poema dello spazio, when the protagonist falls prey to doubt, she ends up asking if perhaps God exists. This is evident in the final part of “Solitudini spirituali”:

E sentiamo, sottilmente, come una febbre, come una droga che ci pervada

tutte le fibre, sentiamo che esiste un punto … un punto dentro di noi

affogato nel nulla … un punto ove tendono tutte le dita del nostro

spirito … un punto solo e fisso … laggi … che non toccheremo mai….

Forse Dio? (19)

On the whole, however, the exaltation of the subject’s energy prevails over the religious impulse. This energy, released through writing, is accompanied by an attempt at breaking the laws of necessity in order to impose a new superhuman system. For the subject, it is a way to fulfill her role of a multiplied woman who presides over ethereal universes, and to determine the course of her own existence by giving voice to her vital impulses. Maria, the protagonist who appears in “La lotta che ho sostenuto con la notte” of Montagne trasparenti, states this clearly. She is not satisfied with the discovery of a connection between herself and the external world. It is not enough, for her, “plasmare” her “cervello” like that of the “notte.” She expects more. She wants to give vent to the “libera esplosione di ogni slancio di impossibilita.” By anthropomorphizing darkness as a “tenebrosa massa cerebrale” but maintaining its presumed unlimited powers, she wants to seize it and put it in her “cranio,” “[per] essere piu certa di riplasmare un nuovo universo,” “[in cui non esistano piu le] irrimediabili schiavit del destino” (77).

When the protagonist’s faith in the triumph of her superhuman power prevails, she tends to avoid references to her body and portrays the vastness of her soul. This suggests an intoxication of power, an exuberance of unconscious forces, a sublimation of desire, and an implied, glad surrender of control. In “Paesaggio interno,” a poetic prose passage belonging to the section “Paesaggi colorati dell’anima” of Montagne trasparenti, the soul is a white canvas upon which the subject’s sensations are painted in words. In her word-painting, Ginanni employs a rich palette: “cerchietti di verde,” “filettature d’oro e d’argento,” “coni di viola, lunghi, lunghissimi,” and “rosso.” These figures, lines and color are described by a sentence within brackets, and they are associated with new objects or depicted in movement. The “coni di viola,” for example, are re-introduced like this: “Montano, montano, respirano oltre la nebbia, oltre la vita, col fiato di infinite boccucce simili a quelle dei pesci assonnati boccheggianti nell’acqua verdemente immota e opprimente delle vasche” (36). All these images reflect an attempt at ascension or escape from something oppressive. They suggest the possibility of overcoming the limits imposed by the body to reach an oneiric dimension, which, in Ginnanni, reveals itself only to a superior, multiplied woman.

The reader travels with the images of ascent presented in the initial part of “Paesaggio interno” and arrives, finally, at a fixed frame seen from above. The figures, lines and color that at first are presented as separated entities, in the end are united within a new spatial configuration: “il rosso serpeggia sul fondo bianco su cui galleggiano i cerchietti verdi; [questi cerchietti roteano] vertiginosamente nella trama delle righe d’oro e d’argento, [poi] si appuntano … come stelline sui lunghi coni di viola …” (37). These words suggest that, as in a flight, the reader has been transported to heights that offer a new and encompassing perspective. Seeing these abstract figures from an aerial point of view serves as a prelude to what will portray the works of Futurist “Aeropoesia” in literature and “Aeropittura” in art. (15) From an exalted vantage point, the narrator of “Paesaggi colorati dell’anima” widens her vision with respect to the people she considers ordinary, and presents a rapidly changing world in its synchrony.

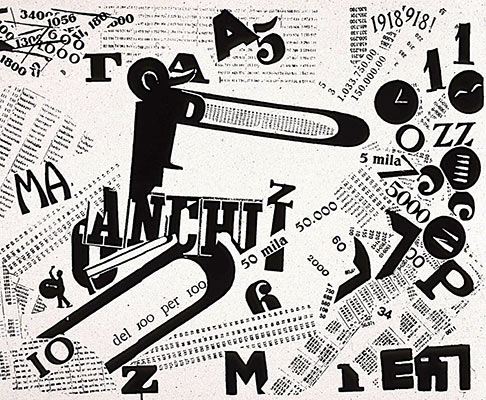

The technique adopted in these poetic prose passages, as in others by Ginanni, does not represent the typographical revolution of Futurist works that were influenced by Marinetti’s notions of “parole in liberta” or “tavole parolibere”: the experimentations of Francesco Meriano and Giuseppe Stainer, for example, or, those of Florentine Futurist women themselves, such as Rosa Rosa, Emma Marpillero and Enrica Piubellini. Instead, Ginanni’s technique relies on an iconic overload of the language. In attempting to break free of traditional referential function, she intuitively seizes upon the atmosphere of a lived situation.

It is worth remembering that, with his “Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista” (1912), Marinetti had encouraged the creation of “parole in liberta”: a new literature based on analogies, which would stress matter instead of subjectivity, and would radically transform conventional linguistic and metric forms (saying yes to the destruction of syntax, to daring analogies, and nouns with their double; saying no to psychology, to adjectives, adverbs, and punctuation). (16) In later manifestoes, Marinetti clarified the principles for “tavole parolibere.” Among many rules stated in these manifestoes three were emphasized: the recovery of onomatopoeia, the renovation of a traditional typographic order, and the inclusion of signs that do not belong to a written linguistic code. (17) The principles exposed in all these manifestoes, which were later collected in Les mots en libert, futuristes (1919), led unavoidably to an emphasis on the visual nature of texts and the simultaneity of fruition. This emphasis, as Luca Somigli rightly observes, “privileges the spatial dimension of the text in opposition to the linear, and therefore time-bound, decoding enforced by traditional syntax” (265).

Departing from Marinetti’s notions in her creative writing, Ginanni undertakes an inner exploration of the self without abandoning syntax. She does not reject the use of different verbal tenses, of adverbs or adjectives; neither does she abandon a linear typographical order or introduce iconographic forms. Like Marinetti, however, she does pair up nouns with telling effect, e.g. “calma-respiro” and “forza-prua” (Montagne trasparenti 21, 23). And again, like Marinetti, she relies heavily on the use of analogies. An example of her technique is seen in the firefly section of Montagne trasparenti. In this section, Ginanni presents fireflies as a sustaining image, and links that image to a myriad of sensations that uplift her soul through forms and colors. A “cascata di lucdole sull’anima” (63) is “corsa rapida di graffiettii rossi segnati con una punta di spillo sopra un cristallo di ametista,” “sillabe iridescenti del firmamento,” “piccoli Chopin di palpiti elettrici,” “istanti luminosi [che] ci danno il senso dell’Infinito col loro ripetersi e ricominciare infallibile, …” (59-63). With these bold analogies, the meaning of “fireflies” widens. It opens multiple perspectives, (18) forging unexpected links among elements usually relegated to separate spheres, including the natural and the cultural. Subjectivity is here dissolved. It is, however, implicitly reconstracted through images evoking sensations that are in harmony with the diffused energies of an imaginary universe.

In a wider context, Ginanni’s representation of a multiplied self through her visual writing may be read as a literary response to the aesthetic theories that dominated the artistic milieu of the Avant-Gardes, even if these theories did not necessarily spring from a similar ideological intent. The simultaneity, the different perspectives and the dynamic sensations evident in Ginanni’s writing reflect the principles proposed in several Futurist manifestoes on art, including “La pittura futurista. Manifesto tecnico” signed by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carra, Luigi Russolo, and others. (19) Ginanni’s use of abstract images recalls much European painting of the same years. (One need only think of works by such artists as Natalia Gontcharova or Liubov Popova.) Therefore, it seems a misleading limitation to connect Maria Ginanni’s abstract tendency to that of Arnaldo Ginna or Vassily Kandinsky, as Glauco Viazzi suggests (368), even though certain points of contact do exist among the three of them. Ginanni does elaborate on Kandinsky’s idea of evolution, expressed in The Spiritual in Art (1912), according to which the prevailing abstract tendency in art mirrors a development of the modern individual’s mind (131-34). And she clearly connects with Arnaldo Ginna, espedally in her desire to move beyond a factual world. Ginna, for example in Pittura dell’avvenire, hoped that the artist would achieve an enormous increase of the “subcosciente’: namely he desired the reaching of a “coscienza-superiore [che dischiude] “un vero piu lontano, piu nascosto ed occulto” (49). Yet Ginanni moves beyond Kandinsky, in that she identifies feeling with an abstract system of colors and forms, and also with a fantastic combination of physical elements. She diverges from Ginna in that she reveals her inner explorations only by probing the possibilities offered by literary language. (Ginna undertook his creative research through abstract painting and cinema, phonetic poems and surreal short stories. Furthermore, unlike Ginanni, he adopted a grotesque, bizarre, and, at times, disturbing imagery.)

With her visual writing, Ginanni thus carves her niche in Florentine Futurism and in other artistic and literary Avant-Gardes of the early twentieth century. By subjugating the senses to the intellect, she projects them onto dynamic architectures of linguistically evoked forms, lines, colors, sounds, and perfumes. By imaginatively transcending the limits of her body; she frees her soul and opens it to a universal spirit. Ginanni’s aesthetic approach contributes to the construction of a multiplied superwoman, one who rejects established female models, and expresses an insistent desire for emancipation. In creating her feminine persona, Ginanni reveals nothing of the provocative, iconoclastic spirit that surfaces in other Florentine Futurist women. (For Irma Valeria, for example, the Shakespearean Ophelia is a “cocotte, con il naso malinconico” [Salaris, Le futuriste 81], and for Fulvia Giuliani, the Romantic Chopin “cade in disgrazia,” and with him so do the “dame ossigenate … (pardon) bionde’ [Salaris, Le futuriste 83].)

Despite those doubts expressed in Poema dello spazio, Ginanni may be defined as a new idealist in that she recreates her world without imitating it, but rather she evokes its spiritual essence while erasing or decomposing her body. In creating this world, she rejects amorous simpering, but she writes lyrically of azure altitudes, little stars, cosmetic powders and fashionable shoes. Yet she never presents models of sweet, submissive mothers. Ginanni’s woman does not preside over domestic spaces; on the contrary, she controls sidereal dimensions. Unlike fatal decadent heroines, she is not the helpless prey of lust; she fuses passion to intellect. She does not wait; she acts. She does not listen; she speaks. Although in the end she remains subordinate to a patriarchal order, she challenges it by cultivating her literary vocation, by forming alliances with other women who are fighting for their rights, and by gaining a central place in the cultural milieu.

Ginanni’s writing shows idiosyncratic traits, but she is united with her Futurist female peers in service to the contradictory cult of a virile woman, a cult rooted in an antidemocratic, militaristic and ultra nationalistic ethos (as is clearly stated in her historical and political writing). Ginanni’s ideas are in agreement with the controversial political program advanced by the Futurist Party in the last number of L’Italia futurista (Feb. 1918). On one hand, this party was progressive, because it called for universal suffrage, divorce, free love and equal pay for women; but on the other hand, it was conservative, because it ignored the dialectics of class struggles. (20) In both her political and creative writings, Maria Ginanni exemplifies what Christine Poggi, in a different context, defines as the “paradox of the Futurist woman.” (21) Although Ginanni never considered herself a suffragette, she fought for new women’s rights as vigorously as many other pre-war feminists did. Unlike them, however, she supported the political directives for the construction of a “master race”–those directives that were to flourish during the Fascist era, and would encourage Italian women to become patriotic “reproducers of the nation” [sic]. (22)

NOTES

(1) In addition to Montagne trasparenti and Il poema dello spazio, Maria Ginanni wrote Le pietre di Venezia oltremare (1930) with Ludovico Toeplitz, in a style recalling D’Annunzio’s. She also announced the creation of the poems later collected in Fabbrica di stelle meccaniche, a drama with Settimelli entitled La macchina, and a couple of novels: Luci trasversali and La disonesta. Please note that in this essay all translations are mine.

(2) Before joining Futurism, the group of L’Italia futurista belonged to the group of “cerebralisti” and “liberisti” (Saccone 90). The distinctive trait of such a group was “l’attenzione per il versante dell’irreale, dell’occulto, del paranormale, estraneo al futurismo marinettiano” (Saccone 92).

(3) Studies concerning Futurist women include: Tabu e coscienza by Anna Nozzoli; Le futuriste by Claudia Salaris; The Other Modernism by Cinzia Sartini Blum; Benedetta Cappa Marinetti: L’incantesimo della luce by Franca Zoccoli; La futurista: Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, guest curator Lisa Panzera; Mothers of Invention, edited by Robin Pickering-Iazzi; “The Transparent Woman: Reading Femininity Within a Futurist Context” by Graziella Parati; “Donne e macchine nell’immaginario scenico del secondo futurismo” by Anna Barsotti; and “Futurism and Feminism” by Lucia Re.

(4) See Mirella Bandini, “Elementi protosurrealisti nei testi di Mario Carli, Bruno Corra e Maria Ginanni in L’Italia futurista,” Italia futurista 17-18; Christine Poggi, La futurista 20; Claudia Salaris, Le futuriste 57, 62; Cinzia Sartini Blum 107; etc.

(5) See, for instance, Antonio Lucio Giannone, “`L’Italia futurista’ e la poetica del `frammento,'” Italia futurista 28.

(6) See, for instance, Lucia Re 263.

(7) See Mirella Bandini, “Elementi protosurrealisti …,” Italia futurista 17; Anna Nozzoli 50; Claudia Salaris, Le futuriste 55, Storia del futurismo 90; Luca Somigli, “Imbottigliature di Primo Conti: un romanzo futurista?” 340; etc.

(8) One of such critics is Glauco Viazzi 368.

(9) Works that have an impact on my approach include Linda Mc Dowell’s Gender, Identity and Places and Roland Barthes’ Mythologies.

(10) In “Il fascismo e le ideologie antifemmimste,” Ezio Santarelli claims that, during the war, Italian women followed different political programs. Most bourgeois women tended to associate gender with a national vision that in certain cases was “panitaliana.”–This seems Ginanni’s case–Unlike bourgeois women, most working class women tended to embrace ideals rooted in an antimilitarist radicalism and a classist massimalism (80).

(11) The mystifying tone in this article, and the attribution of positive values solely to her countrymen have unavoidable consequences for her representation of those who are not “Italian heroes.” When Ginanni refers to the men of enemy armies, she uses all sorts of derogatory epithets. In an article entitled “Cannoni d’Italia” (Italia futurista 4 Mar. 1917: 1), for example, Austrians and Germans are defined as “idioti” or “pedanti.” Without even the pretense of objectivity, she depicts these men as individuals devoid of “genialita,” an attribute that Ginanni associates with the “razza italiana.”

(12) Marja Harmannaa traces a precise genealogy of Marinetti’s multiplied man. Among other things, she claims that Marinetti’s new man is connected to a former character of the super man: a mythical figure that appeared in late eighteenth–century literature, and was later retaken in philosophy. (Un patriota che sfido la decadenza 280-82). The qualities of this exceptional man, born from the union of man and machine, were already assumed by some of Marinetti’s literary characters. For instance, in the novel Mafarke le futuriste (1910), the male protagonist Mafarke himself gives birth to his son Guzurmah, and Guzurmah is described as a new extraordinary creature: a winged and mechanical man.

(13) See Anna Nozzoli 51; Lucia Re 263.

(14) In the “Preface” to Poema dello spazio, Ginanni hints at the intent of this book, which is different from that of Montagne trasparenti. She explains that Poema shows “rarefazioni e tremiti che pervadono con equilibri ed intuizioni campi d’incertezza e di incoscienza: l’ignoto spirituale ed universale” (7).

(15) A couple of relevant documents concerning such a Futurist trend are the “Manifesto of Aeropainting” signed in 1929 by Balla, Depero, Prampolini, Marinetti, Benedetta and others (Humphreys 73), and the “Manifesto of Aeropoetry” appeared in the journal Gazzetta del popolo on October 22, 1931 (Salaris, Le futuriste 200).

(16) Sec Isabella Gherarducci 34-35.

(17) Luigi Ballerini declares that, while analyzing practical examples, one frequently observes an “osmosis” between parole in liberta and tavole parolibere (72). He also points out that with such manifestoes by Marinetti, what is favored is “un’investitura linguistica di materiali segnici non verbali,” [che portano al] “riconoscimento di un loto potenziale grammatologico” (173).

(18) Ginanni’s approach fits well a trend that Clara Orban singles out in twentieth-century art and literature. According to Orban, this trend shows that “words and images began to be evaluated in a formal way. They were placed together on the work of art to capitalize on their divergent semiotic properties, to create polyvalent sign-forms” (3).

(19) “La pittura futurista. Manifesto tecnico” was signed on April 11, 1910.

(20) In Futurism and Politics, Gunter Berghaus offers a detailed account of the different Futurist political alliances. The contradictions inherent in the program of the Futurist Party have been mentioned in other critical works, including Claudia Salaris’ Storia del futurismo 113.

(21) Christine Poggi, along with others, has pointed out the paradoxical role of Futurist women. In her article “The Paradox of the Futurist Woman” in La futurista: Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, she declares that, given the “notorious misogyny and antifeminism” of Futurism, “[t]he term `futurist woman’ may appear to be an oxymoron, a historical impossibility” (17).

(22) Lesley Caldwell uses this expression in “Reproducers of the Nation: Women and the Family in Fascist Policy” 110.

Sica, Paola – Maria Ginanni: futurist woman and visual writer – 2002