Wynne Nevinson Christopher Richard

(English)

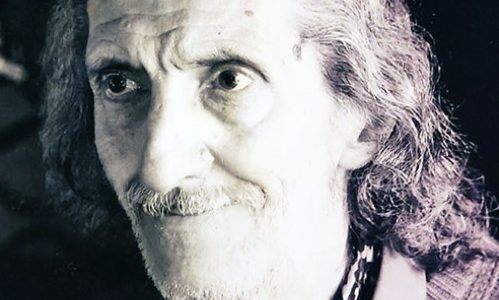

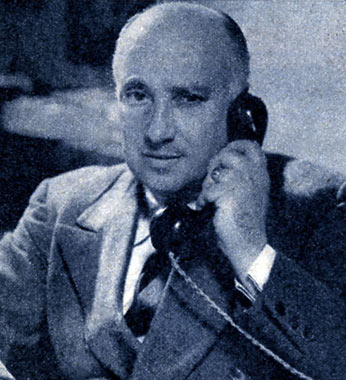

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (13 August 1889 – 7 October 1946) was a British figure and landscape painter, etcher and lithographer, who was one of the most famous war artists of World War I. He is often referred to by his initials C. R. W. Nevinson, and was also known as Richard.

Nevinson studied at the Slade School of Art under Henry Tonks and alongside Stanley Spencer and Mark Gertler. When he left the Slade, Nevinson befriended Marinetti, the leader of the Italian Futurists, and the radical writer and artist Wyndham Lewis, who founded the short-lived Rebel Art Centre. However, Nevinson fell out with Lewis and the other ‘rebel’ artists when he attached their names to the Futurist movement. Lewis immediately founded the Vorticists, an avant garde group of artists and writers from which Nevinson was excluded.

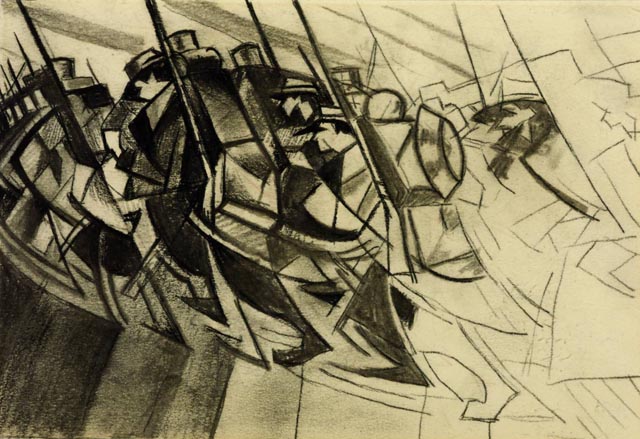

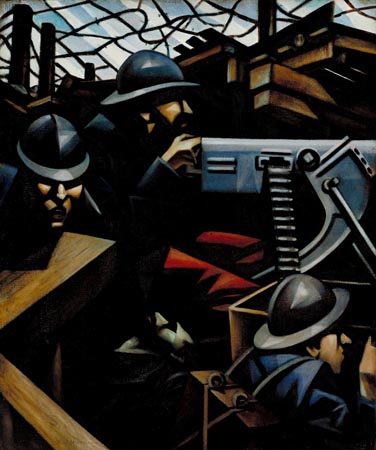

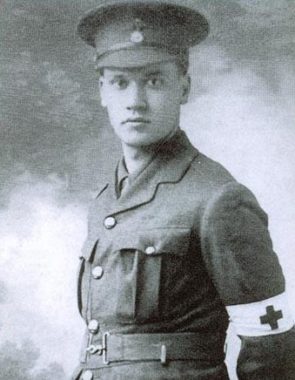

At the outbreak of World War I, Nevinson joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and was deeply disturbed by his work tending wounded French soldiers. For a very brief period he served as a volunteer ambulance driver before ill health forced his return to Britain. Subsequently Nevinson volunteered for home service with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He used these experiences as the subject matter for a series of powerful paintings which used the machine aesthetic of Futurism and the influence of Cubism to great effect. His fellow artist Walter Sickert wrote at the time that Nevinson’s painting La Mitrailleuse, ‘will probably remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting.’ In 1917, Nevinson was appointed an official war artist, but he was no longer finding Modernist styles adequate for describing the horrors of modern war, and he increasingly painted in a more realistic manner. Nevinson’s later World War One paintings, based on short visits to the Western Front, lacked the same powerful effect as those earlier works which had helped to make him one of the most famous young artists working in England.

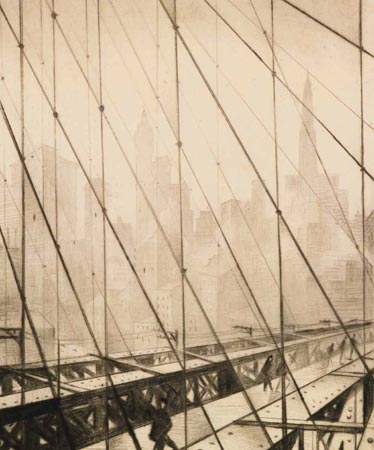

Shortly after the end of the war, Nevinson travelled to the United States of America, where he painted a number of powerful images of New York. However, his boasting and exaggerated claims of his war experiences, together with his depressive and temperamental personality, made him many enemies in both the USA and Britain. In 1920, the critic Charles Lewis Hind wrote of Nevinson that ‘It is something, at the age of thirty one, to be among the most discussed, most successful, most promising, most admired and most hated British artists.’ His post-war career, however, was not so distinguished. Nevinson’s 1937 memoir Paint and Prejudice, although lively and colourful, is in parts inaccurate, inconsistent, and misleading.

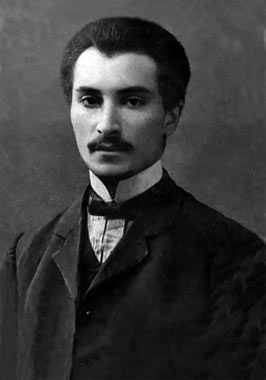

Richard Nevinson was born in Hampstead, the son of the war correspondent and journalist Henry Nevinson and the suffrage campaigner and writer Margaret Nevinson. Educated at Uppingham School, which he hated, Nevinson went on to study at the St John’s Wood School of Art. Inspired by seeing the work of Augustus John, he decided to attend the Slade School of Art, part of University College, London. There his contemporaries included Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Adrian Allinson and Dora Carrington. Gertler was, for a time, his closest friend and influence, and they formed for a short while a group known as the Neo-Primitives, being deeply influenced by the art of the early Renaissance. Gertler and Nevinson subsequently fell out when they both fell in love with Carrington. Whilst at the Slade, Nevinson was advised by the Professor of Drawing, Henry Tonks, to abandon thoughts of an artistic career. This led to a lifelong bitterness between the two, and frequent accusations by Nevinson, who had something of a persecution complex, that Tonks was behind several imagined conspiracies against him.

After leaving the Slade, Nevinson studied at the Academie Julian in Paris throughout 1912 and 1913 and also attended the Cercle Russe. He met Vladimir Lenin and Pablo Picasso, shared a studio with Amedeo Modigliani and became acquainted with Cubism. While in Paris he also met the Italian Futurists Marinetti and Gino Severini. Back in London he became friends with the radical writer and artist Wyndham Lewis. When Wyndham Lewis founded the short-lived Rebel Art Centre, which included Edward Wadsworth and Ezra Pound, Nevinson also joined. In March 1914 he was among the founder members of the London Group. In June 1914 he published, in several British newspapers, with Marinetti, a manifesto for English Futurism called Vital English Art. Vital English Art denounced the “passéiste filth” of the London art scene, declared Futurism as the only way of representing the modern, machine age and proclaimed its role in the vanguard of British art. Lewis was offended that Nevinson had attached the name of the Rebel Arts Centre to the manifesto without asking him or anyone else in the group. Lewis immediately founded the Vorticists, an avant garde group of artists and writers from which Nevinson was excluded, though he devised the title for the Vorticists’ magazine, BLAST.

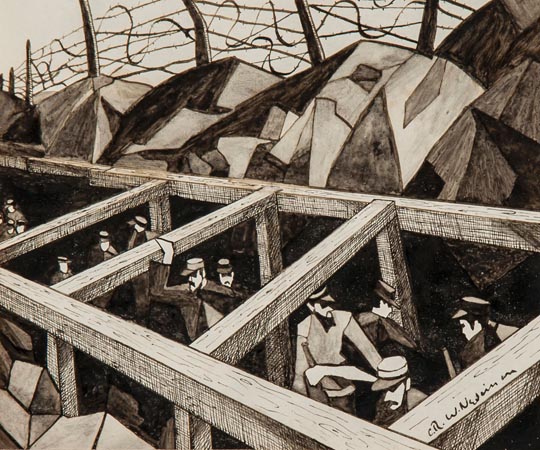

Nevinson had four pictures included in the Second Exhibition of the London Group held in March 1915. Nevinson’s Futurist painting, Returning to the Trenches, and the sculpture The Rock Drill by Jacob Epstein received the most attention and greatest praise in reviews of the show. Nevinson spent the rest of 1915 working as a Royal Army Medical Corps private at the Third London General Hospital in Wandsworth. Despite its name, the 3rd LGH was a specialist centre for the treatment of both shell shock and severe facial injuries.

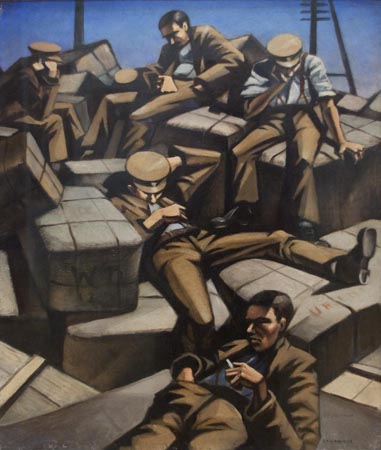

Nevinson used his experiences in France and at the London General Hospital as the subject matter for a series of powerful paintings which used Futurist and Cubist techniques, as well as more realistic depictions, to great effect. In March 1916 he exhibited his painting La Mitrailleuse with the Allied Artists Association at the Grafton Galleries. His fellow artist Walter Sickert wrote at the time that La Mitrailleuse ‘will probably remain the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting.’

The reaction to La Mitrailleuse prompted the Leicester Galleries to offer Nevinson a one-man show which was held in October 1916. The show was a critical and popular success and the works displayed all sold. Michael Sadler bought three paintings, Arnold Bennett bought La Petrie and Sir Alfred Mond bought La Taube which showed a child killed in Dunkirk by a bomb thrown from a type of German plane known as a Taube. Several famous writers and politicians visited the exhibition; it received extensive press coverage and Nevinson became something of a celebrity.

In April 1917, with the support of Muirhead Bone and his own father, Nevinson was appointed an official war artist by the Department of Information. Wearing the uniform of a war correspondent, he visited the Western Front from 5 July to 4 August 1917, a period which included the start of the Battle of Passchendaele on 31 July. Nevinson was billeted with other visitors in the Château d’Harcourt, south of Caen.

When he returned to London in August 1917, Nevinson first completed six lithographs on the subject of Building Aircraft for the War Propaganda Bureau portfolio of pictures, Britain’s Efforts and Ideals, and then spent seven months in his Hampstead studio working up his sketches from the Front into finished pieces. A number of officials from the Department of Information visited the studio and soon began complaining about these new works. Nevinson was now focused on individuals, either as people displaying heroic qualities or as victims of warfare. He did this by painting in a realistic manner using a limited colour palette, sometimes only mud-brown or khaki. Whereas for his 1916 exhibition Nevinson had displayed both realistic works and pieces using Cubist and Futurist techniques, for his 1918 exhibition all the works were realistic in style and composition.

At the start of World War Two the British Government created the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, WAAC, and appointed Kenneth Clark as its Chairman. Despite the public hostility between Clarke and himself, Nevinson was disappointed not to be offered a commission by WAAC. He submitted three paintings to WAAC in December 1940 which were also rejected. He worked as a stretcher-bearer in London throughout the Blitz, during which his own studio and the family home in Hampstead were hit by bombs. WAAC eventually purchased two pictures from him, Anti-aircraft Defences and a depiction of a fire-bomb attack, The Fire of London, December 29th – An Historic Record. Nevinson obtained a commission from the Royal Air Force to portray airmen preparing for the Dieppe raid in August 1942 and they also allowed him to fly in their planes to develop pictures of the air war. He presented a painting, a cloudscape entitled The Battlefields of Britain, to Winston Churchill as a gift to the nation and which still hangs in Downing Street. Shortly afterwards a stroke paralysed his right hand and caused a speech impediment. He applied for a junior clerical post with WAAC and was refused. Nevinson taught himself to paint with his left hand and had three pictures shown at the Royal Academy in the summer of 1946. He attended that exhibition, with the assistance of his wife Kathleen, in a wheelchair but died a few months later aged fifty-seven.